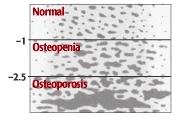

Like their names suggest, osteopenia and osteoporosis are related diseases. Both are varying degrees of bone loss, as measured by bone mineral density, a marker for how strong a bone is and the risk that it might break. If you think of bone mineral density as a slope, normal would be at the top and osteoporosis at the bottom. Osteopenia, which affects about half of Americans over age 50, would fall somewhere in between.

Osteopenia and bone density test

The main way to determine your bone density is to have a painless, noninvasive test called dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) that measures the mineral content of bone. The measurements, known as T-scores, determine which category — osteopenia, osteoporosis, or normal — a person falls into (see graphic).

Fracture risk increases as bone mineral density declines. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2001 reported that a 50-year-old white woman with a T-score of -1 has a 16% chance of fracturing a hip, a 27% chance with a -2 score, and a 33% chance with a -2.5 score.

But there isn’t a huge difference between, say, a -2.3 T-score and -2.5, although the former would be labeled osteopenia and the latter, osteoporosis. “The label matters less than the number. These distinctions are to some extent arbitrary lines in the sand,” says Dr. Maureen Connelly, a preventive medicine expert at Harvard Medical School. Regardless of your exact score, if your bone density results fall into the osteopenia category, your doctors will probably schedule you for a bone mineral density test every two to five years.

What’s your bone density score?

A T-score ranging from -1 to -2.5 is classified as osteopenia. The lower the score, the more porous your bone.

Osteopenia Prevention

Everybody’s bones get weaker as they get older. But certain choices and habits accelerate the process. They include:

- not getting enough calcium and vitamin D

- smoking

- drinking too much alcohol

- using certain medications, such as corticosteroids and anticonvulsants

- not getting enough weight-bearing exercise (at least 30 minutes on most days). If your feet touch the ground during an exercise, it’s probably weight bearing. Running and walking are weight bearing. Swimming and biking are not.

Women are far more likely to have low bone density than men, but it’s no longer viewed as solely a women’s condition. About a third of white and Asian men over age 50 are affected. The percentages for Hispanics (23%) and blacks (19%) are lower, but still sizable.

Should I get a bone mineral density test?

Experts disagree about who should get their bone mineral density measured because it’s not clear that the benefits justify the cost. Consider this: 750 tests of women between the ages of 50 and 59 would need to be done to prevent just one hip or spine fracture over a five-year period. From a societal point of view, is that worth it?

Currently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends testing for:

women 65 and older

postmenopausal women younger than 65 who have one or more risk factors, which include being thin

postmenopausal women who have had a fracture

If you aren’t in one of these categories yet, don’t wait until you are to start doing some weight-bearing exercise. Some “uplifting” activity now might prevent frail bones later.

For men, testing is done more on a case-by-case basis.

Osteopenia treatment

Osteopenia can be treated either with exercise and nutrition or with medications. But some doctors are increasingly wary about overmedicating people who have osteopenia. The fracture risk is low to begin with, and research has shown that medication may not reduce it that much. We also don’t know if the medications might have some long-term effects. So if your T-score is under -2, you need to be sure you are doing regular weight-bearing exercise, and you are getting enough vitamin D and dietary calcium. If you’re closer to -2.5, your doctor may consider adding medication to keep your bones strong.